Mona Hatoum: Unveiling Veracity in Disguise

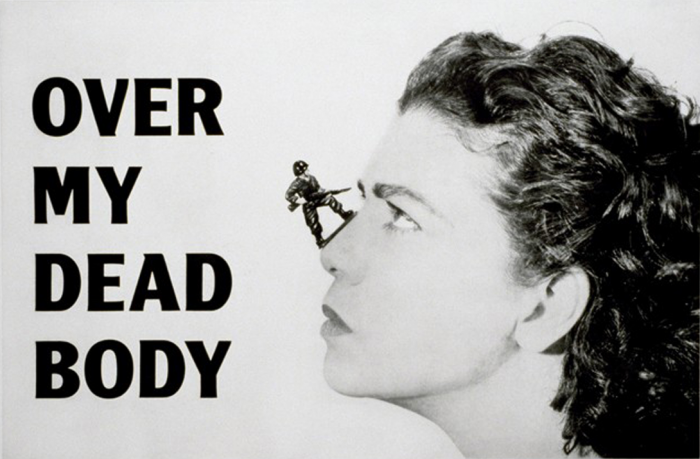

Mona Hatoum, Over My Dead Body, 1988

Billboard, ink on paper, 204 x 304 cm.

© Mona Hatoum

Adapting Mona Hatoum in a few words; pulling from personal encounters in Egypt, to an invitation to speak about her video work at the Menil Collection.

The Western video art movement emerged as a dynamic fusion of installation, sound, and performance art during the transformative decades of the 1970s and 80s, marking a pivotal moment in the trajectory of contemporary art. While the roots of video art can be traced back to the late 1960s, it was during the subsequent decades that its potential was fully realized. In the 1980s, the movement experienced a significant amplification, with a shift towards emphasizing physicality alongside experimentation. Artists like Gary Hill, American farther of video art, epitomized this evolution, pioneering a freestyle approach to videography and producing groundbreaking single-channel tapes that transcended traditional boundaries. Hill's electronic media, characterized by their immersive nature and incorporation of interactive installations, redefined the role of the moving image, transforming it from a confined screen experience to an expansive projection of space and perception, immersing the viewer in the moving image.

The prelude of speaking to the father of video art, a man I drove across the Qasr El Nil bridge from downtown Cairo, Egypt, during his collaborative exhibition with Beirut-born, to exiled Palestinian parents, London-based Mona Hatoum, networked by technology and exile, and Egyptian-born, New York-based industrial designer, Karim Rashid, coined by Time Magazine as the “Prince of Plastic,” in a 2006 exhibition called "Kairotic" curated by Stuttgart and -German-Delta-Egyptian artist, Susan Hefuna. Kairotic in Greek, meaning "the right moment," encapsulated the significance of this convergence. Whether in the form of mundane household furniture, contrasted against luxury goods, craftsmanship, and technology, it showcased the intense engagement of three artistic giants and their relationship to the body, Hatoum had created Misbah, and Waiting is Forbidden, two of the works showing below and had shown at the Menil, to showcase the craftsmanship of Egyptian street signages with a play on words, and the lantern is a dark satire reminiscing the holy month of Ramadan lantern epitomized by light reflections of soldiers and explosions replacing the cultural geometry and spiritual glee. This stance resonates distinctly by installations, prints, and audio-visual works to socio-political narratives, prioritizing truth over conventional aesthetics.

Left to right:

Mona Hatoum, Waiting is Forbidden, 2006, Enameled metal plaque, 30 x 40 cm.

Mona Hatoum, Misbah (“lantern” in Arabic), 2006, Fixture plate, metal chain and electric motor 220 V, 56 × 32 × 28.5 cm.

Hatoum's video works intricately weave figurative and symbolic illustrations, adapted to the moving image medium while retaining their regional cinematic essence, a point Latif Adnane, Moroccan film critic, further explores. Her art poignantly juxtaposes endless paradoxes: struggle versus tranquility, conformity versus insurgency. Hatoum's work navigates the complexities of reality and surreality, subtly disguising itself in the familiar to unveil concealed, disturbing truths. Her deeply personal and socially conscious knowledge stems from the psychology of displacement and reoccurrence, evident in seminal works like So Much I Want to Say, Changing Parts, and Measures of Distance, which freeze moments of displacement in poignant visual narratives. Behind seemingly mundane objects like decorative hand grenades disguised as murano glassware (see below Nature morte aux grenades), playing off of Henri Matisse’s still life, Nature morte aux grenades, word “grenade” means pomegranates in French lies a provocative commentary challenging the Palestinian ethnic cleansing, epitomizing Hatoum's commitment to freedom and truth in the face of political and social constructs; architects in the relevance of intense engagement.

Mona Hatoum, Nature morte aux grenades (detail), 2006-2007, crystal, mild steel, and rubber, 95 × 208 × 70 cm, The Heinz Family Fund and Katharine Ordway Fund.

© The Yale University Art Gallery

Two things that highlight our discussion here are the figurative and symbolic illustrations captured in the video works of Mona Hatoum. That doesn't mean it doesn't co-exist in her installations and performances but is adapted to fit the needs of the moving image, and as Latif Adnane will digress into further, regional cinematography. A socio-political narrative adopts the short-lived screen. The aesthetics are not about being beautiful but bold and valid, and, in those aspects of boldness and truth for Mona Hatoum's work, an ugly truth may appear.

Hatoum's work juxtaposes the concept of an endless paradox: a struggle versus tranquility, conformity versus an insurgency. My favorite works of art are captured in such parodies. A constant grappling with reality, and in her case, surreality, and then locating the placement of the self and the identity around such transformation.

A maverick of meanings, Hatoum's work subtly disguises itself in the familiar, only to draw attention to the known and bruise the knowledge when realization identifies something concealed, disturbing, and accurate. The truth is what is most striking with her work; even though this is her take, her surreality, it's never less the truth. A visual truth, an unspoken truth, a repressed and silenced truth. The taboo of knowledge is to speak of what you know. Her knowledge is very personal and socially conscious, resulting from the psychology of displacement and reoccurrence.

In 1984 and 1988, she did two video production residencies at the Western Front Art Center in Vancouver and created the works So Much I Want to Say, Changing Parts and Measures of Distance over 6 years. Her work, Roadworks, was originally part of a street performance she had done in Brixton in 1985 that then evolved into the video piece that then again developed into a series of performance stills illustrating that hour-long movement through the street, barefoot and heavy with boots tied to her feet, dragging the resistance behind her. People stop and stare at the act, and then carry on with the a regard of irrelevance. Hatoum had frozen moments of her displacement in these visual narratives. Only moments, observed as lifetime experiences, present the intimacy and isolation of each encounter the artist experiences with an object or the body.

Mona Hatoum, Roadworks, Performance Still 1985–95

Video VHS, colour 6min 45s. Collection Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’art moderne, Paris.

Tate © Mona Hatoum

In the case of So Much I Want to Say, she uses herself again in this process of being through a transmission, silenced by male domination, in an attempt to eliminate her physical presence, but only accentuates it more. In Measures of Distance, her mother is the object, the subject, and the frozen still of literal distance, isolation, and displacement. The script of a mother writing letters to her daughter, who is held away from her because a war broke out, is further illustrated with stills of Hatoum's mother showering, bare, exposed, an Arab woman, bare and exposed in the most intimate way, a mother bare and exposed to her daughter, to the world. Wrapped with words, a letter she writes to her daughter of her difficulties, the change, the harmony, and disruption that come off as barriers of distance, like the barbed wire hanging in Impenetrable, her bond with her mother, the privacy that occurs between them is pretty confidential, as her father is barely illustrated in the letter, a discretion; resisting the colony and the patriarchy, and yes, also fighting the distance with those words.

In Changing Parts, another video screening at the Menil during the Terra Infirma exhibition, shows a static and long slow movement focusing on one location of tiles, offering a stalemate, a no man's land, while Bach's Cello Suite #4 plays in the background. A poetic simplicity united with a minimalist layout is presented in this hors-d'oeuvre of emotions. Listen, but do not feel. Feel but do not taste. Taste but do not touch; touch but do not occupy. Occupy but do not take over, and so on and so forth. Bach continues to illustrate the dislocation of romanticism. Something so minute contrasted up against something quite massive and potentially disturbing that you no longer feel the need to taste but only trap, occupy, antagonize, and repeat.

What does that say about distance and orientation? A subtle, aesthetically pleasing violence lurks behind the most simple and mundane. A table display of decorative glass-blown hand grenades, a hair necklace, and boots of resistance dragged by bare feet. Her placement is so definitive that it breaks the labels of her ethnic and gender identities, hence the success of freedom and truth in the constant wake of social and cultural relevance.

Author: Aïda Eltorie

Originating from the film screening under the auspices of the Palestine Film Festival, Houston, Texas at The Menil Collection, Terra Infirma, Mona Hatoum solo exhibition. Work was originally written in November 17, 2017 for the screening, and readapted on May 11, 2024.

Watch a video response to the billboard, Over My Dead Body, provided by the Wakeforest University Art Collection.